Just over two hundred years ago, it was a stormy June on Lake Geneva in Switzerland. Lord Byron and his personal physician, John Polidori, were renting out a mansion in the summer, the Villa Diodati. Rained in with them at the time were poet Percy Shelley and Mary Godwin, who would later marry Percy and be known as Mary Shelley.

They read Shakespeare and Mary’s mother (Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin) and a host of German ghost stories to beat the boredom. Then Byron issued a challenge: each of them should write a ghost story of their own, and then share it with the group.

Each of the four tackled the challenge in their own way. Mary Shelley wrote about their creative endeavor in her introduction to Frankenstein.

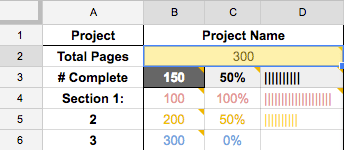

Polidori, Byron, Mary Shelley, and Percy Shelley

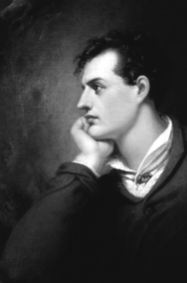

Lord Byron

Byron wrote a story based on a fragment of a tale from the end of his poem “Mazeppa,” which itself was a narrative poem based on a legend of a historical Ukranian high commander. If that isn’t literary inception, I’m not sure what would be, especially if you consider the fate of this abandoned vampiric tale, which later inspired:

John Polidori

Polidori “had some terrible idea” of a skull-headed lady who saw something she shouldn’t—Mary couldn’t remember what. Polidori didn’t know how she should be punished for such a crime, so he put her in the tomb where Romeo and Juliet died.

After Byron abandoned his ghost story when the weather improved, John rewrote it into The Vampyre, a novella which basically became the grandfather of all paranormal romance.

Percy Shelley

Mary’s future husband, Percy, was a poet “more apt to embody ideas and sentiments in the radiance of brilliant imagery and in the most melodious verse that adorns our language than to invent the machinery of a story.” In other words, he was a literary pantser who cared little of plot.

Percy took something that scared him as a child and added some alternative facts to fashion his ghost story.

Mary Godwin (Shelley)

With her high literary pedigree, it’s no surprise that Mary Shelley would become a writer herself. But as a child, rather than the romances or adventure stories that were popular at that time, she preferred living in a world of her own making, inspired more by her dreams and imagination than reality. “I could people the hours with creations far more interesting to me at that age than my own sensations,” she writes.

Mary struggled with the challenge. The men, she felt, failed at writing a true story, concerning themselves more with word choice or concepts than creating an experience.

“I busied myself to think of a story, —a story to rival those which had excited us to this task. One which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror—one to make the reader dread to look round, to curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart. If I did not accomplish these things, my ghost story would be unworthy of its name. I thought and pondered—vainly. I felt that blank incapability of invention which is the greatest misery of authorship, when dull Nothing replies to our anxious invocations. Have you thought of a story? I was asked each morning, and each morning I was forced to reply with a mortifying negative.”

The poets quickly abandoned the challenge, neither finishing because they were “annoyed by the platitude of prose.” Byron and Shelley instead spoke about a number of topics, including the principle of life, and if it could be discovered or created. They spoke of Dr. Erasmus Darwin’s “Spontaneous Vitality” and of galvanism, a professor of medicine’s applications of electricity to dead frogs, making their legs move.

That night, Mary couldn’t sleep. “My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me,” she says. She saw vividly the scene of a “pale student of unhallowed arts” using a machine that brought a “hideous phantasm of a man” to life.

“The idea so possessed my mind, that a thrill of fear ran through me, and I wished to exchange the ghastly image of my fancy for the realities around. I see them still; the very room, the dark parquet, the closed shutters, with the moonlight struggling through, and the sense I had that the glassy lake and white high Alps were beyond. I could not so easily get rid of my hideous phantom; still it haunted me. I must try to think of something else. I recurred to my ghost story, my tiresome unlucky ghost story! O! if I could only contrive one which would frighten my reader as I myself had been frightened that night!

“Swift as light and as cheering was the idea that broke in upon me. “I have found it! What terrified me will terrify others; and I need only describe the spectre which had haunted my midnight pillow.” On the morrow I announced that I had thought of a story. I began that day with the words, It was on a dreary night of November , making only a transcript of the grim terrors of my waking dream.”

It was Percy Shelley who, seeing its potential, urged Mary to flesh it out (pardon the pun) and turn it into what became the grandmother of science fiction novels.

Which Geneva Gothic Romantic Writer Are You?

It depends on how you get your inspiration.

The Reteller

Polidori was inspired by the works of others, of Shakespeare and Lord Byron, creating his own stories from their initial ideas. Consider stories that inspire you. Write fan fiction, a retelling, or a twist on another tale, making it your own.

Polidori was inspired by the works of others, of Shakespeare and Lord Byron, creating his own stories from their initial ideas. Consider stories that inspire you. Write fan fiction, a retelling, or a twist on another tale, making it your own.

Example: Marissa Meyer wrote Sailor Moon fanfiction before she started writing her debut novel Cinder (a futuristic retelling of Cinderella), followed by retellings of Little Red Riding Hood, Rapunzel, Snow White, and the Queen of Hearts from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

The Historian

Byron was inspired by literary history, both his own and historical legends. Consider something you’ve written in the past or a legend or classic you find fascinating. Then write it in a different medium or genre. Turn a play into a poem, a myth into a novel, or a short story into a script.

Byron was inspired by literary history, both his own and historical legends. Consider something you’ve written in the past or a legend or classic you find fascinating. Then write it in a different medium or genre. Turn a play into a poem, a myth into a novel, or a short story into a script.

Example: Till We Have Faces by C. S. Lewis is based on the myth of Cupid and Psyche. Rick Riordan writes novel series based on mythology.

The Memoirist

Percy wrote creative nonfiction, taking creative liberties with memories of true and personal events and feelings. What events in your past had the most significant emotional reactions, psychological consequences, or philosophical epiphanies? How can you fictionalize or elaborate on those moments?

Percy wrote creative nonfiction, taking creative liberties with memories of true and personal events and feelings. What events in your past had the most significant emotional reactions, psychological consequences, or philosophical epiphanies? How can you fictionalize or elaborate on those moments?

Example: Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane is his most autobiographical , most chilling, and most beautifully written novel.

The Inventor

Mary was inspired by science, dreams, and philosophy. To come up with fantastic ideas like hers, read widely and think wildly. Read about scientific discoveries, consume philosopher theories and poet anthologies. Absorb visual and performance art. Visit a museum and take notes. I just stumbled upon a special on PBS about how engineers and scientists are using the concepts of origami to build structures, automate robotics, and energize space stations. How could you incorporate origami into a fictional universe?

Mary was inspired by science, dreams, and philosophy. To come up with fantastic ideas like hers, read widely and think wildly. Read about scientific discoveries, consume philosopher theories and poet anthologies. Absorb visual and performance art. Visit a museum and take notes. I just stumbled upon a special on PBS about how engineers and scientists are using the concepts of origami to build structures, automate robotics, and energize space stations. How could you incorporate origami into a fictional universe?

Example: Publisher’s Weekly calls Haruki Murakami’s Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World a literary pyrotechno-thriller.

A New Challenge

Ideas may be illusive, but they aren’t endangered. I’m probably more of a Byron or Polidori than a Shelley, but inspiration can come from anywhere.

Now I challenge you to write a story. It doesn’t have to be a ghost story, but it does have to come out of a deep emotion. Will it be dread? Anxiety? Betrayal? Regret? Obsession?

Write your story, and if you feel so lead, tell us about it in the comments. If you post the story on your blog or a website, link to it below. Maybe you’ll find a critique partner!